Part one – the current context

In this first of three blogs by GuildHE’s Chief Finance Officer Mark Taylor, we look at the current financial position of higher education institutions in the light of the continued freeze in the regulated fee, recent material changes in costs as a result of inflation, and emerging evidence of some stalling or even reduction in demand from both home and overseas students.

The question of funding higher education has been in play since the inception of the 1992 Further and Higher Education Act, which transferred the responsibility for the former Polytechnics and Teacher Training Colleges away from Local Education Authorities to centralised funding.

The history since 1992 – something I will consider in my second blog – can be characterised by cyclical erosion of the real value of the unit of resource followed by ‘fixes’, which in turn then lose value to the point of further adjustments being needed. There has therefore been no real sustainability in funding to this point.

Having been through one of the longest periods of frozen funding for home students, we are now at the point of criticality again, needing at the very least an adjustment to ensure that the impending real instability in the system is averted. The complicating factor this time has been the political inertia around HE funding, fed in part by the timing of the next general election, and also the result of years of a political and mainstream media view that students pay too much for too little.

The OfS report Financial sustainability of higher education providers in England 2024 summarises the current set of forecasts as follows:

“Overall, providers are forecasting deterioration in the short- to medium-term financial outlook. Their data returns show that the sector’s financial performance was weaker in 2022-23 than in 2021-22, and is expected to decline further in 2023-24, with 40 per cent of providers expecting to be in deficit and an increasing number showing low net cashflow.”

“Our modelling suggests that no growth across the sector could leave nearly two-thirds of institutions in deficit by 2026-27, with 40 per cent facing low liquidity at year end. For the reasonable worst case scenario we have modelled – which assumes a significant reduction in international student numbers and no cost cutting activity – over 80 per cent of institutions would be in deficit and nearly three quarters would face low levels of liquidity.”

How the current funding system has started to fail

The real terms fall in the value of the £9,250 was initially masked both by a widening of the market, and a period of low inflation. However, post 2015/16 the system started to falter due to external factors beyond the sector’s control.

Firstly from 2016 to 2020 there was a sharp decline in the number of school leavers eligible for entry to higher education. At the same time the part time degree and mature student markets had been decimated by higher fees and hesitancy to take on student loans. Part time undergraduates fell from 590,000 in 2008/09 to 290,000 by 2016/17, a fall of 51%.

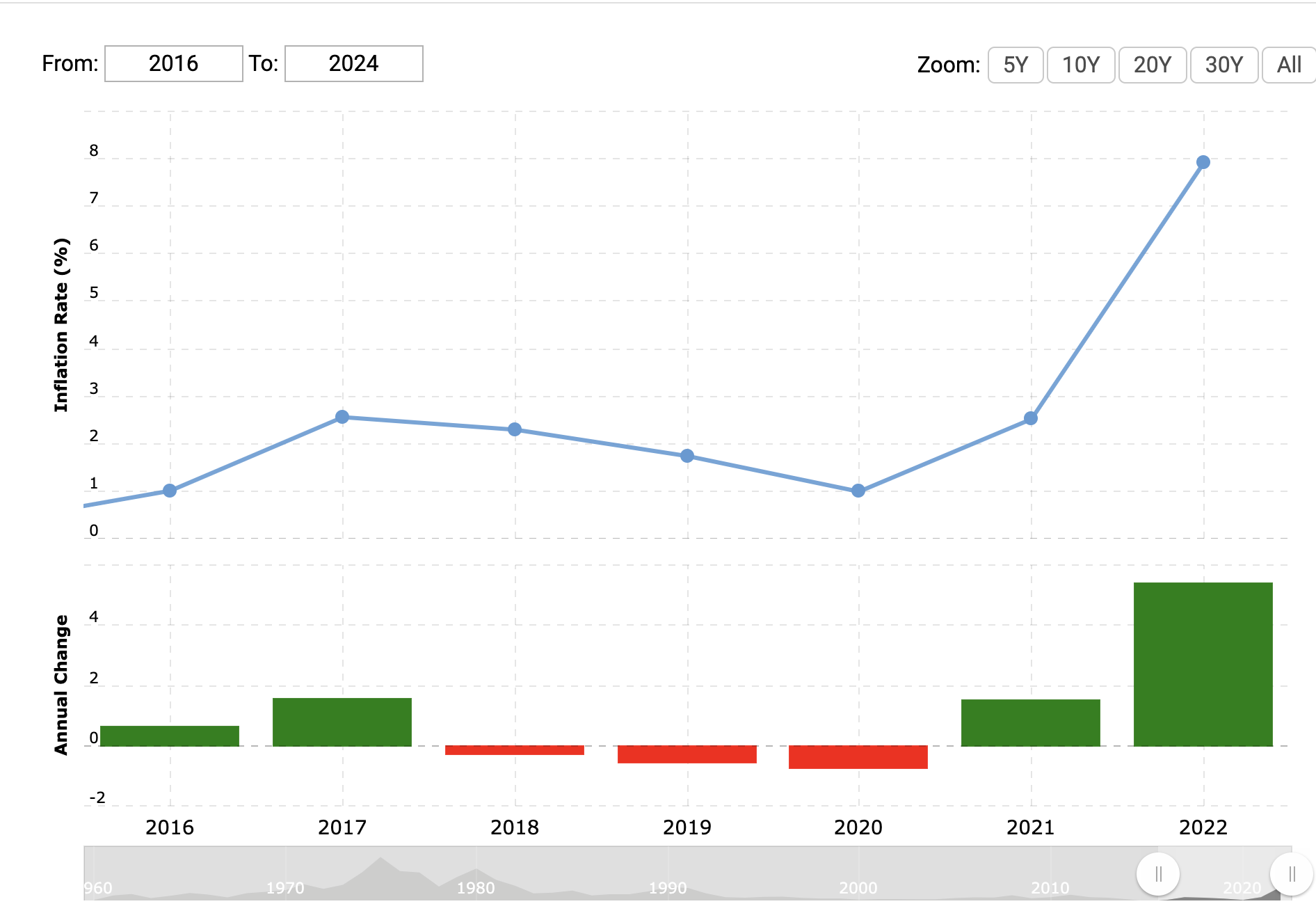

Just at the point where the number of 18 year olds started to rise again inflation, which had not previously been a noticeable problem, rose very substantially and quickly:

From £9,250 previously looking “expensive” the sharp decline in the real value of the unit of resource has become the primary issue.

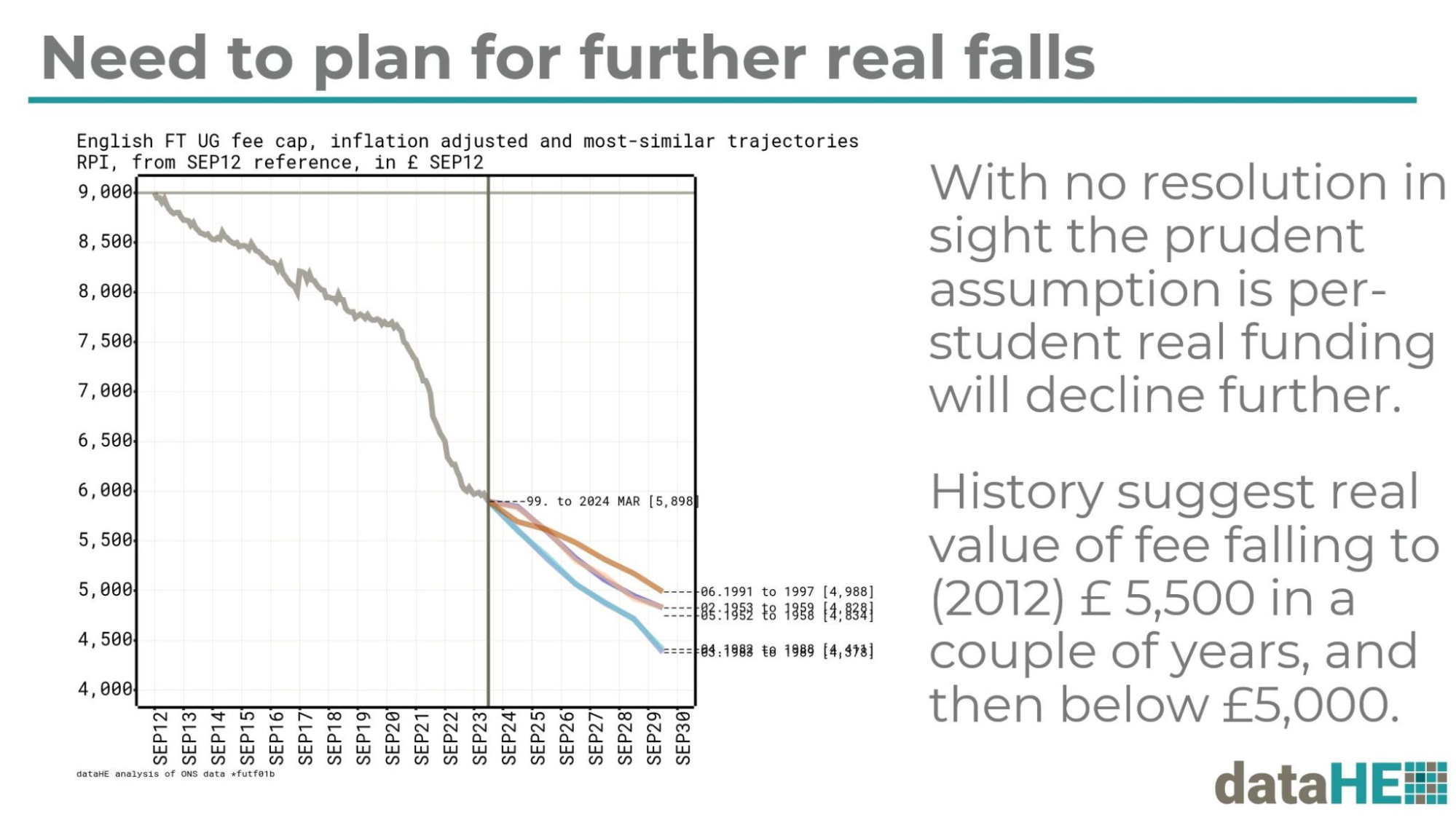

Mark Corver of DataHE has described the latest value of the fee falling below the value of £5,900 as a milestone.

“The latest inflation data gives another grim milestone for UK universities – the real value of the full time undergraduate fee cap has fallen below £5,900 in 2012 pounds for the first time, way below the £9,000 level in 2012 and taking the sector into increasingly uncharted waters for funding.

In 2024 money that means a shortfall against 2012 levels of around £4,900 for each student for each year of teaching– so needing to deliver a student to graduation for £15,000 less (in £2024) cost than a decade ago.

This is already in mission impossible territory, but for university leaders the true situation is harder still. This is because they need financial plans for the future, and with no visibility of a funding solution they are duty bound to act on the basis of things getting worse. In our analysis historical precedents show that without intervention real fee values dipping to £5,500 in a couple of years or so.

It is difficult to estimate comparable figures for per-student funding before 2012 but our analysis suggest that the nadir, in the late 1990s, was the equivalent of a fee cap of around £5,600 (in £2012). And that low point was very brief, with values already recovering ahead of the big jump in 2012.

This is increasingly leading to cutting the cost base now, often meaning staff , with worries the resulting damage may be hard to recover…”

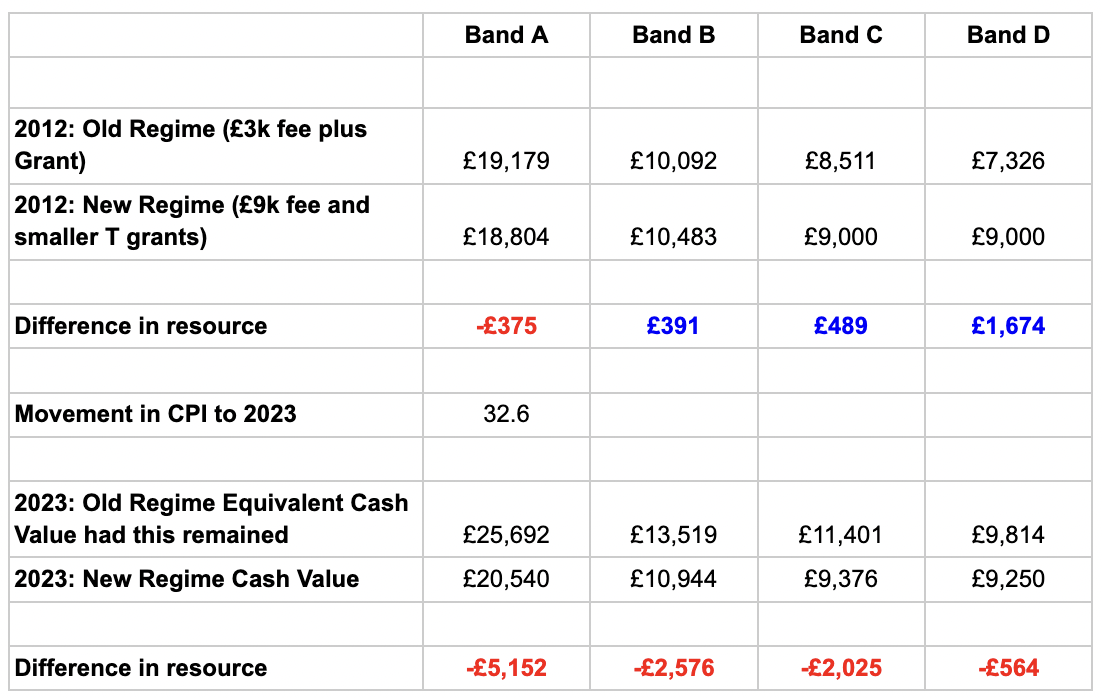

The simple table below compares the unit of resource (fee plus grant) in 2012 vs 2023 across price bands. This indicates that had the previous £3k fee plus grant been maintained, only Band D remains comparable to the current level of resources:

How is the sector responding?

The number of institutions engaged in staff reduction exercises has increased markedly over the last year. The unintended consequences of maintaining a frozen regulated fee cap could include:

- A further reduction in face to face teaching

- Changes in assessment and feedback, increasingly using AI to save costs

- Further reductions in intakes of home students at top universities in favour of overseas students

- Closure of high cost provision in favour of increasing subjects with lower costs of delivery. The OfS has analysed the difference in relative growth across subjects and concludes: “The growth in business and management, law and social sciences correlate with those subject areas that are often considered less expensive to deliver, where there is greater demand and where less specialised facilities and equipment are required for students’ learning.” The QAA has also highlighted that high quality education costs money to deliver.

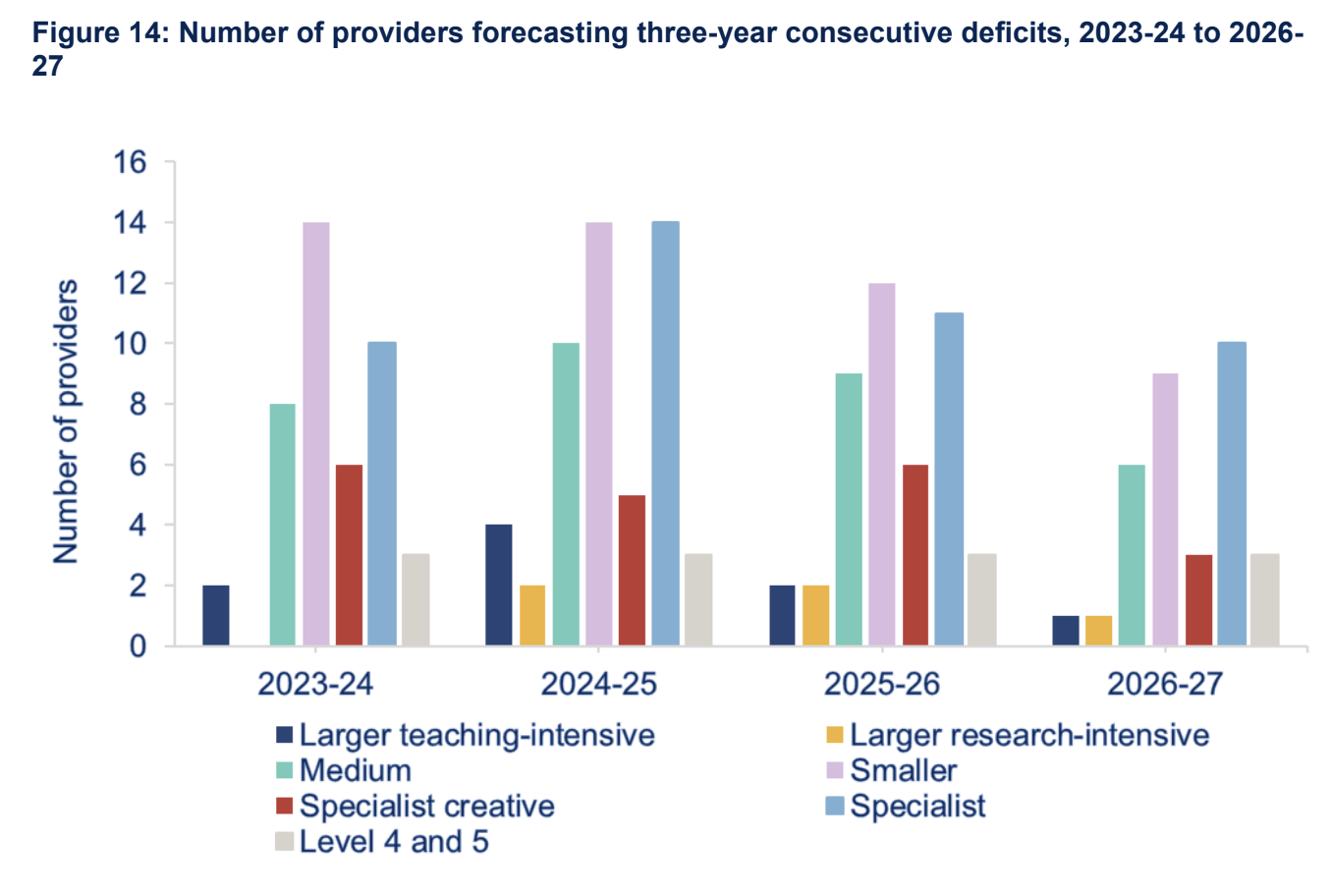

- A loss of diversity, choice and specialism within the sector. The graph below from the OfS Report suggests that specialist and smaller institutions are particularly at risk

This analysis is very concerning. Guildhe’s mission is to ensure that we preserve the diversity of higher education providers in the UK system, something which is enshrined in HERA. Without action we are in danger of eroding our rich higher education ecosystem made up of world-leading and highly impactful specialist institutions and HEIs that offer a distinctive student experience.

In part two we explore the impact of higher education funding models over the last 30 years, from Dearing to Augar and beyond.